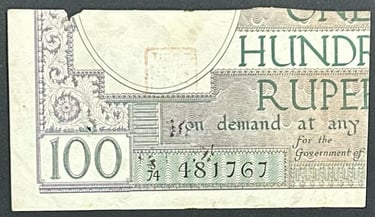

British Burma King George V 100 Rupee Quarter Cut Note

King George V 100 Rupee Quarter Cut Note from British Burma and India. True purpose of the part of the banknote fragments for accounting & Japanese chop mark.

9/3/20256 min read

The King George V 100 Rupee Quarter Cut Note issued for British India and British Burma are among the most fascinating and historically significant artifacts in the realm of South Asian numismatics. These partially destroyed and often chop-marked fragments of colonial currency provide a compelling window into the complex interplay of monetary administration, wartime financial chaos, and the eventual dissolution of British rule in the region.

For decades, their purpose was obscured by conjecture. Some believed they circulated as fractional denominations; others thought they were improvised wartime issues. Only in recent years, through careful archival research in the records of the Reserve Bank of India and the British colonial administration, has their true story—a blend of bureaucracy, emergency, and survival—been revealed.

The King George V 100 Rupee Note: A Pillar of British India's Financial System

To appreciate the significance of these quarter notes, it is necessary to understand the role of the original 100 Rupee banknote. For over fifty years, from 1886 to 1937, Burma was governed as a province of British India. As such, its monetary system was not independent but instead linked to the wider Indian economy and regulated under the various Indian Currency laws.

The 100 Rupee note of King George V was the highest commonly encountered denomination in circulation below the ultra-high 1000 and 10000 Rupee issues used mainly in interbank and government transfers. These large notes were essential for tea, rice, oil, and timber companies in Burma, as well as for the functioning of the colonial administration.

A distinguishing feature of the KGV 100 Rupee note was the absence of the familiar "Government of India" heading at the top center. Instead, the issuing authority was identified by the name of one of seven issuing circles—Bombay, Calcutta, Cawnpore, Karachi, Lahore, Madras, and Rangoon. The Rangoon circle, naturally, served Burma.

Over the years, subtle variations in typography and signatures occurred. Collectors can identify at least two font styles for the circle names (small and large green type) and three issuing officials—H. Denning, J. B. Taylor, and J. W. Kelly—whose signatures mark different printings. These nuances, overlooked by the general public, now provide numismatists with crucial classification tools for dating and authenticating surviving notes.

From Union to Separation: The Evolution of Burma’s Currency

The Government of Burma Act of 1935 set the stage for a dramatic shift. As of 1 April 1937, Burma officially separated from British India, a move that necessitated its own distinct monetary system. The Burmese Monetary Arrangements Order of 1937 was the legal framework for this transition, and its first major step was to differentiate the existing currency.

Instead of issuing new banknotes from scratch, which would have been a massive logistical undertaking, the British authorities decided on a provisional solution: overprinting existing Indian notes. This measure allowed for a smooth transition and ensured a stable supply of currency. For the 5 Rupee, 10 Rupee, and 100 Rupee King George V notes, the phrase "Legal Tender in Burma Only" was added.

KGV 100 Rupees Black Overprint (Type 1)

Initially, these overprints were in black ink. For the 100 Rupees, the overprint was placed below the "Rangoon" issuing circle on the front and at the lower center on the reverse, they were a subtle but crucial marking. However, this method proved to be impractical. The black ink was often difficult to see on the note's dark, intricate design, especially under poor lighting or when the note was worn. This posed a significant problem for merchants and officials who needed to quickly verify a note's legal status. Serial ranges for this type are T/32 (700001–1000000) and T/41 (000001–100000), though forged overprints are known to exist outside these ranges.

KGV 100 Rupees Red Overprint (Type 2)

To solve the visibility problem, the authorities switched to a more visually striking and legible red overprint. This new text was boldly positioned at the upper margin of both the front and back of the note, outside the main printed frame. The change was both a practical and symbolic one, signaling the beginning of a new, independent monetary identity for Burma. The red overprint notes are found in prefixes and serial range T/41 (100001–1000000) and T/47 (000001–606000).

This overprint phase is an important transitional chapter, bridging Burma’s financial subordination to India. For more on this transition, see our dedicated article on the King George V Burma Overprint Banknotes.

The Numismatic Mystery of the Quarter Cut Notes

Perhaps the most intriguing aspect of this story is the appearance of quarter portions of 100 Rupee notes—almost always the lower-left corner, preserving the serial number. For many years, collectors speculated about their function. Some proposed they circulated as “25 Rupee” notes during the shortages of World War II. Others suggested they were part of an emergency issue by the retreating British.

Documents from the Reserve Bank of India and British military records revealed the true purpose of these fragments: they were accounting remnants. According to the strict financial protocols of the British administration, when high-value notes—including the 100, 1000, and 10000 Rupee denominations—were officially canceled, redeemed, or exchanged, they were not destroyed in their entirety. Instead, three-quarters of the note would be incinerated or shredded, while the bottom-left quarter, which contained the critical serial number, was retained.

These fragments served as a physical record, a bureaucrat's way of marking a transaction and ensuring a transparent paper trail. This procedure explains why some of these quarter pieces are found pasted onto blank backing paper, while others are not. Both types, however, represent the same thing: remnants of a methodical accounting process, never intended for circulation and held no monetary value. It is a widely accepted fact within the numismatic community that the other three corners of these banknotes have never surfaced in the market.

Wartime Survival and the Japanese Chop Marks

The story of the quarter notes takes a dramatic turn with the outbreak of World War II and the subsequent Japanese invasion of Burma in 1942. The advance of the Imperial Japanese Army forced the British to evacuate, and in a desperate measure to deny the invaders financial resources, British officials were ordered to destroy all currency.

Arthur Potter, the Financial Controller of Burma, issued directives to district officers to burn or shred all paper notes and to bury or submerge coins in water bodies. Despite these efforts, some currency inevitably survived. The quarter notes, already cut and set aside, were among the artifacts that emerged from the chaos, often in the hands of looters or even found among the possessions of Allied prisoners of war.

The most intriguing element of these wartime survivors is the Japanese chop mark. The exact reason for these marks remains a historical enigma, but they are widely believed to have been applied by the occupying Japanese forces. The marks may have served a variety of purposes: to authenticate captured assets, to catalog seized funds, or simply as an internal administrative notation. Whatever the intent, the chop mark transforms a simple accounting remnant into a powerful symbol of the brutal struggle for control over Burma and its resources.

A Guide for Collectors: Identifying Quarter Note Varieties

The study of these quarter notes is a specialized field within numismatics. Collectors can differentiate between various types based on a number of factors:

Absence of Overprint: Some quarter notes, particularly those from early series with prefixes like S/74 and T/25, show no overprint text. These are fragments of the original Indian notes, cut for accounting purposes before the Burma-specific overprints were implemented.

Black Overprint: Notes from the T/32 prefix series, for example, may show a partial black overprint on the reverse, as the text was placed at the lower center of the note, a section often included in the cut fragment.

Red Overprint: Curiously, quarter notes from the red overprint series (e.g., T/41) do not display the red text. This is because the red "LEGAL TENDER IN BURMA ONLY" was located at the top margin of the note, which was the section destroyed during the cutting process.

Date Stamps: Many of these fragments bear black ink date stamps (such as 31, 34, and 37 believed to be 1931, 1934, and 1937), which likely correspond to internal treasury dates of cancellation or verification.

Japanese Chop Marks: The most prized variety is one that bears a clear Japanese chop mark, which is a rare and highly sought-after feature that attests to its direct link to the wartime occupation.

These quarter notes are more than collectibles; they are micro-historical documents. Each fragment, with its unique combination of prefix, overprint, date stamp, and potential chop mark, tells a unique story about a time of profound change. They are a physical record of the end of a colonial era, the chaos of war, and the intricate financial systems that underpinned it all. For numismatists and historians, they are a window into the past, each piece a tangible link to a story of emergency, survival, and two empires in conflict.